One of the most common – and most loaded – questions English teachers hear is:

“Which English is correct — British or American?”

It’s a question that reflects a deeper anxiety learners often feel: they want to speak “proper” English, to fit in, to be taken seriously. But as teachers, our role isn’t just to answer the question – it’s to help them see why the idea of a single, universal “standard” is more complicated (and more interesting) than they might think.

In this article, I draw on my own teaching and training experience – as well as research from applied linguistics – to explore what “Standard English” really means today, why it matters, and how you can help your students make informed, confident choices without being boxed in by myths about correctness.

What exactly is “Standard English”?

In its strictest sense, Standard English refers to the codified, prestige variety of English used in education, publishing, and public life in a particular country. It’s the variety you see in school textbooks, official documents, and national broadcasting. In the UK, this means British spelling and grammar conventions (colour, centre, use of the present perfect for recent events). In the US, it means the equivalent American norms (color, center, preference for past simple).

These standards didn’t emerge by accident – they developed over centuries through historical, social, and institutional processes. And importantly, they’re not neutral:

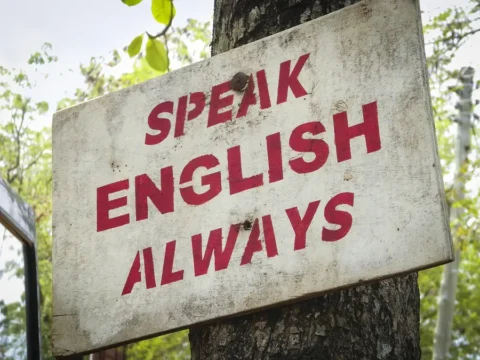

- In much of the world, British English became the standard because of Britain’s colonial power and its influence on education systems.

- In the 20th century, American English rose to global prominence thanks to the US’s cultural, economic, and political dominance, spread through Hollywood, advertising, technology, and academia.

- Even within countries, the “standard” variety often reflects the speech of an educated urban elite – and can marginalise regional, working-class or minority dialects.

For example, in India and Singapore, local varieties of English include vocabulary and structures shaped by regional languages – yet in many formal education settings, these forms are still discouraged or marked as “incorrect” rather than recognised as legitimate in their own right.

Why does Standard English matter in the classroom?

Even though no one speaks perfectly standard English all the time, it still matters – particularly for learners aiming to succeed in specific contexts. Here’s why.

Academic contexts

Universities and exams such as IELTS, TOEFL, and Cambridge proficiency tests expect consistent use of a recognised standard. An essay that switches between colour and color or programme and program can appear careless. Teaching students to choose one standard and use it consistently is crucial for academic success.

Professional contexts

Employers – rightly or wrongly – often equate standard English with competence. A CV, business email, or presentation riddled with inconsistencies or non-standard forms can undermine a candidate’s credibility, even when the message is perfectly clear.

Social mobility

For many learners, mastering a prestige variety of English opens doors to opportunities abroad, in government service, or with multinational companies.

That’s why giving students a solid grasp of the standard is useful – it helps them succeed in contexts where it’s still expected.

British, American… or something else?

It’s easy to frame the choice as British vs. American – but the reality is more nuanced. Learners may also encounter Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, or South African English, each with its own recognised standard. Helping learners choose depends on their personal goals.

Example scenarios:

- A student applying to a US university should focus on American spelling and usage because that’s what admissions officers expect.

- A learner training as a tour guide in Spain for mostly British tourists should learn British vocabulary and idioms (lorry and holiday rather than truck and vacation).

- A professional in Singapore working for a multinational with both US and UK clients needs to understand and accommodate both.

- A call centre agent in the Philippines may need to adjust their speech to match American customers while recognising British idioms.

- A content creator on TikTok targeting a global audience benefits from knowing which forms resonate in which markets – and may even deliberately mix them for effect.

English is always evolving – and students need to keep up

Even among native speakers, people rarely speak the formal standard consistently. They:

- Use informal syntax (You coming? instead of Are you coming?).

- Drop “whom” entirely in favour of “who.”

- Use region-specific vocabulary – for example, soda (US), pop (Midwest US/Canada, parts of northern England), and fizzy drink (UK) all refer to the same thing.

And English continues to evolve – especially under the influence of internet and youth culture. Learners are exposed to:

- Abbreviations and acronyms from messaging and gaming: LOL, BRB, IYKYK.

- Memes and TikTok slang: slay, stan, mid, based.

- Hashtag-driven idioms: #blessed, #cringe, #sorrynotsorry.

- Inclusive language trends — such as they as a singular, gender-neutral pronoun.

For learners consuming English on social media, in YouTube comments, or during online gaming, this evolution is their lived reality – and it’s worth acknowledging and even incorporating some of these trends into your lessons.

And it’s not just slang and internet culture that can catch learners off guard. Many students experience a real shock when they encounter natural, unsimplified English for the first time – the kind spoken by taxi drivers, waiters, or colleagues in casual settings. In class, we often slow our speech or enunciate more clearly to aid comprehension. That’s understandable – if students can’t follow us, they can’t learn. But over time, this “classroom English” can create unrealistic expectations about how English actually sounds in the real world.

Think about how children acquire language. They don’t start by learning neatly separated words from a textbook – they absorb language through sound, rhythm, and repetition. When a parent says, “What are you going to do?”, what the child hears is often closer to “watcha gonna do?”. They understand the meaning long before they’re aware that the phrase contains six separate words. Only later, through reading and formal learning, do they begin to unpack the grammar behind what they’ve already internalised through speech.

It’s a useful reminder for teaching adults, too. Learners benefit from hearing real, connected speech – even if they don’t catch every word at first. If their only exposure is to slow, overly articulated classroom English, they may struggle when faced with fast, natural conversation outside the classroom. Just as children rely on rhythm and pattern before understanding structure, language learners need to hear how English actually sounds in everyday use.

Why exposure to multiple varieties is valuable

Even if learners need to focus on one standard for formal purposes, they’ll still encounter others – in emails, social media posts, gaming chats, Netflix shows, livestreams, and YouTube tutorials. Today’s learners are surrounded by English in ways previous generations weren’t.

By exposing students to more than one variety, you:

- Build listening comprehension by helping them recognise different accents and idioms.

- Prepare them for real-world communication with speakers from different backgrounds.

- Encourage flexibility and confidence.

Feedback from students who face exposure in these different contexts can highlight the gap between classroom English and the reality learners face – and the opportunity we have as teachers to bridge it.

Another important aspect of this exposure is the influence of the teacher’s own accent and learning background. Many learners are first taught English by non-native instructors whose pronunciation reflects their own linguistic experience – for example, a Hong Kong teacher using British English with a Cantonese accent, or a teacher in Turkey who studied in Australia. This layering of accents and varieties can shape how learners perceive and process English, and may lead to challenges later when encountering unfamiliar accents like American English.

Rather than seeing this as a disadvantage, it highlights the importance of helping students become comfortable with a range of Englishes – including the version spoken by their teacher. Integrating different accents into listening practice and encouraging open discussion about accent variation can go a long way in building students’ confidence and comprehension skills.

Teaching strategies for navigating Standard English

Here are some classroom-tested strategies for balancing standard forms with real-world awareness.

- Integrate expectations naturally

If your school has a preferred standard, make it clear through your corrections, materials, and models. You don’t need to announce it on day one – just reinforce it consistently. - Teach “register”

Show students the difference between formal and informal English, and explain when standard English is expected. Something as simple as comparing a WhatsApp message to a cover letter can be effective. - Explain differences, don’t condemn them

When students use an alternative word or spelling, explain where it comes from instead of calling it “wrong.” This keeps the atmosphere positive. - Encourage consistency in writing

Ask learners to pick a standard for written work and stick to it. Mixes like color and centre can look sloppy even if they’re understandable. - Use authentic, varied materials

Include real emails, podcast clips, TikTok captions, and livestream excerpts – not just scripted textbook dialogues. This helps students hear what English actually sounds like. - Model open-mindedness

Your attitude matters. If you model respect for different varieties, your students are more likely to do the same.

Beyond British and American: World Englishes

Finally, remember that most English speakers today live in countries where English is not a native language – and those communities have developed their own norms and standards of English.

Linguist Braj Kachru’s Three Circles of English model illustrates this, dividing global English usage into:

- Inner Circle: Countries where English is native and functions as the dominant standard (e.g. UK, US, Australia).

- Outer Circle: Post‑colonial countries where English is institutionalized and shaping local norms (e.g. India, Singapore, Nigeria).

- Expanding Circle: Countries where English is learned mostly as a foreign language for international communication (e.g. China, Brazil, Russia).

This framework shows that English is not owned by native speakers alone – different societies develop their own effective norms. Kachru’s model supports the idea that Standard English is just one of many valid standards, shaped by history and function. You can read more about this concept on Wikipedia or in this IATEFL blog post by Penny Ur.

Kachru’s model highlights the reality that English is used across a wide range of local and global contexts – often shaped by different histories, identities, and communicative needs. This challenges the assumption that native-speaker norms should always be the benchmark. In many international settings, effective communication matters more than following any one “standard.” As linguist Jennifer Jenkins puts it, the goal of English as a global language is “intelligibility, not conformity”.

Final thoughts

Our job as teachers isn’t to impose one “correct” variety of English – it’s to help students communicate effectively in the contexts that matter to them. By giving them a clear understanding of what Standard English is, when to use it, and how to handle other varieties, we set them up for success. And by exposing them to the rich diversity of English as it’s really used, we help them appreciate that English isn’t just a language – it’s a global conversation.

If you’ve had experience teaching different varieties of English, navigating accent challenges, or supporting learners in adapting to real-world English use, I’d love to hear your perspective. What approaches have worked for you? Have your learners struggled with particular varieties or adapted more easily than expected? Feel free to share your thoughts, classroom experiences, or questions in the comments below.

Sources and References

- Crystal, D. (2019). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and Identity. Oxford University Press.

- Kachru, B. B. (1992). The Other Tongue: English Across Cultures (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press.

- World Englishes – Wikipedia overview

- Ur, P. (2019). “English as a Lingua Franca – Implications for Teachers.” IATEFL BETA Blog.

16 comments

Bruce

Oh dear! How on earth are we going to survive if we do not have a benchmark? Imagine my Upper Intermediate and Advanced classes being exposed to Cockney London and then having to speak at a job interview! Imagine a foreign speaker paying good money to learn to speak English when all they are taught are hybrid versions. No! Teach English as it should be taught and then let students compare with the wannabee versions! Why on earth must we continue to drop the ideal to accommodate the easiest route forward? We had fun with two lessons of Cockney English and then reverted to that which has made the English language a major part of the global village’s communication network.

Barry

This is a good discussion point and in principle I agree with the main point – spoken language is rarely correct grammatically!! From a different perspective, however, I am a student of Thai as well as a teacher of English. As a student I need to know the foundations of the language I am learning if I am going to master it in all forms – written and spoken. Once I know the basics I am happy to explore the idiomatic and dialectical differences… I think a balance is needed and not dogmatics on either side of the discussion!

Holcat

The beauty of English is that it is the world lingua franca. Different regional variations apply in their locations and appropriate contexts. Therefore, it is essential for students, and indeed all of us, to know and be able to speak standard English. Exposure to regional variations is important but must be subordinate to standard English. Otherwise a person from India, who has learned British English, and its associated reduced and liaised forms, would never be able to communicate with a person from China, who has learned American English and its associated reduced and liaised forms. Teach standard English first and teach reductions and liaisons as a bonus.

EFL student

I learned English as a Foreign Language and I understand exactly what you are all trying to say. I am glad I have learned the correct Queen’s English first. It is very difficult to understand native speakers but only at the beginning. Later, when the ears are tuned into intonation and rhythm of spoken English, listening skills really progress. I am sure learners must know grammar (with contractions) before being exposed to “wachagonnado”. I prefer to know what is behind this word before I can actually hear it. This way I will feel more confident to use it. At the elementary level teaching English has to be descriptive. Later, when students know the basics they can cope with the idea of many Englishes. It is easier to learn spoken English without the strict grammatical rules, you can do it by yourself based on the correct English learned in the classroom.

Idiomista

The most sensible comment here comes from the EFL Student:

“I prefer to know what is behind this word before I can actually hear it”. Of course. Learning a second language is not like learning your first – unlike very small children, EFL students want to know what they are saying and why: if they are using a contraction, or regional speech, they need to understand what they are doing, and the original structure from which the contraction derives.

Exposing students to regional speech patterns and accents is great, but should not be confused with teaching basic structures. Encouraging students to say ‘wanna’ simply because they are having a problem remembering to put the ‘to’ with the infinitive is crazy. ‘Wanna’ and ‘gonna’ are heard in casual US speech, which of course is as valid as any other form of spoken English, but educated Americans don’t write ‘wanna’, and even if your students never intend to write much English, they should be able to write something as simple as ‘I want to see you tomorrow’. The student who applies for a job in any English-speaking country, including America, and writes ‘I wanna work here. You are gonna like my approach’, is doomed to fail!

Also, ‘wanna’ sounds very unnatural coming from non-US speakers, even more so if they already have a strong French/Spanish/Japanese accent. Do them a favour and teach your students the basic structure of the language first, and let the regional and colloquial usages develop naturally.

Anonymous

It seems obvious to me that students need to learn how English is constructed, and how to speak it. It is simple. “I want to” is written just like that, where in American English, it is said “I wanna.” I would never encourage anyone to write “I wanna” because it is simply wrong, but if they choose to say “I wanna” I certainly will not correct them. Like wise, if a student were to say “I want to” there is no problem. Is it not the goal of the teacher to give the student that most options? Is a language not learned both by writing and speaking? The author makes a great point, but he has missed the most important reason that any student takes a class, To learn a language. Take time to teach your students grammar, speech, and listening. Why can it not simply be said “It is wrote this way, and sometimes said and heard in multiple ways” Get off your high horse and teach the students, not what is right or wrong, but what it is!

Anonymous

I have learned German over the past years and am surprised to say that I learned more from living in Germany, for the short amount that I did, than I did studying the language. I could not understand a word when I arrived in Germany, even after studying for a year. If someone would have taught me the way Germans actually speak in everyday language, I wouldn’t have had to waste a year of studying. As far as teaching goes, I think it would be more effective to teach how English works and tell students that this form is correct and formal, then teach them other informal ways. If the students know the difference then they will not be sitting in an interview using what they know as informal, but they would obviously use formal.

David

I generally point out usage variations, especially for spelling. My shortcut on the whiteboard is to prefix them with US > and UK >. Some of the most useful structured speaking practice books available to us come from the USA. Being Australian, though, most of our material comes from British or Australian sources, ensuring that spelling is consistent with the local scene. However, many English students here are from South Korea, where their previous English training has usually been American-based. We’ve no choice but to address differences, because perceptive students will be experiencing them even as we study. One aside: I know “debate” as a verb can be either transitive or intransitive, but don’t we normally omit the preposition when there’s an invitation to “debate a subject”?

Robert

I really enjoyed the article. I taught in Japan and the rivalries between teachers who were protecting their version of English was a great source of banter! Being from the UK, a popular one was always “Colour has a U in it!!!

Becky

I teach at a language school in Germany where there is a fair amount of debate as to which is ‘better’. A colleague of mine even went as far as suggesting to his students that they don’t use British English at all, because American English is more global (he said because of Hollywood, American English is seen and heard more often – a moot point in Germany where everything is dubbed). He also used to correct their (southern) British pronunciation of words like bath and laugh. My opinion – the more exposure to different varieties of English, the better. But it should be focused to the students’ needs. If their more likely to do business with the UK or study there (i.e. most of Europe) then British English should be more stressed.

Phil

Hiberno-English is my mother tongue. I began to teach British English in 1993. I enjoy the differences between the many forms of the language however, my task as a teacher is to enable my students use the language in their lives. Exposure to the various forms can be useful if the student has a good grasp of one form, an interest in or need for the other forms. The question of accent and pronunciation is also a thorny one and possibly a more difficult one to resolve. Philips history lesson is naïve and insulting. Look at any English dictionary the influence of other cultures on the English language is clear. History culture, language and tradition are fluid if they are static they are dead!

Jennifer

As English speakers, we all have our preferences as to which English we teach. To us, the differences are profound, but we are still able to navigate them. I think exposing students to a variety of English serves them best. Think about learning a new language yourself; the differences that a native speaker can easily distinguish are gibberish to you! I recently lived in Japan and learned standard Japanese from a textbook and a highly educated woman. In class I could speak and understand, but in the outside world, the language was impossible for me. After bumbling through for 5 1/2 months thinking I would never be able to understand and communicate in Japanese, I took a trip to a large city. I was SHOCKED that I could understand and use my language training. I thought that maybe everything had crystalized for me. Four days later I returned home and realized that I was just as lost as before. I always thought it was me who was the problem, but really, it was the fact that the area I was living in had a very different accent and dialect than standard Japanese. I was training my ear to recognize standard Japanese but that’s not what I was hearing!

Long story short, we should recognize that we are there to help people communicate and not teaching EFL in order to propagate our own regional form of English.

PS. One of the language classes I took over couldn’t understand me because I had a “strange” accent. (I have a standard Canadian accent–not the fake “Americans making fun of Canadians”) Their previous teacher was from Mississippi and pronounced my name as “Gin”ifer. To most English speakers he was the one with the strange accent!

Anonymous

In my opinion, I feel that is important to learn the “standard” of English that pertains to your region and teach others the same way you have been brought up to speak the language. The main goal is to transmit knowledge to others, whether that’s in American English or Canadian English; the fruit of the matter is that it’s English!

Bob

I’m in an MA TESOL program in San Francisco CA. I am doing a case study of an ESL learner whose L1 is Cantonese. What I don’t see in this excellent discussion of various “forms” of English (e.g., Australian, American, British, etc.) is the effect a particular instructor’s own accent may have on learning English. My case study subject was taught English 1st in Hong Kong by a Cantonese instructor with a heavy Cantonese accent. She was taught British English and with a British accent, but by a Hong Kong native whose L2 is Cantonese. Then she was taught ESL in succession by a Cantonese who learned English in Toronto, then a Cantonese who learned English in Australia, and lastly a native American instructor. She speaks of difficulties in understanding American-accented English after education in a British-accented English and the other varieties of accents of her instructors. I can’t find much in the ESL literature about this subject.

Keith Taylor

Bob – You raise a really important and often under-discussed point. You’re absolutely right that a teacher’s own accent and language background can have a significant impact on learners’ listening development and expectations, especially when they encounter new varieties later on. I’ve added a paragraph to the article to reflect this – just after the section on exposure to different Englishes – to highlight how learners are often first introduced to English through teachers with diverse linguistic experiences, and how this shapes their journey. It’s something many of us encounter in practice, and I appreciate you drawing attention to it.

Derek Dorsett

Mr. Lewis,

I was trained in CELTA to speak normally, but I am not sure what research supports this. I tend to agree with you as far as your assertation, however, can you point me in the direction of supported research that indicates speaking normally is beneficial to the learner? I’m not sure how I will see your response, so would be willing to email it to me?